THE STORY: (57 minutes) This episode, pivotal to the entire Trojan War Epic, features philosophy, bedroom farce, and genuine tragedy — all in equal measure. Temptation plays the lead: Agamemnon tempts Achilles; Hera tempts Zeus; and Patroclus tempts Deadly Destiny.

THE COMMENTARY: WERE ACHILLES & PATROCLUS LOVERS? (20 minutes; begins at 57:00) I dedicate this entire post-story commentary to the Achilles/Patroclus relationship: a relationship which has confounded scholars, storytellers, and listeners for the past 3500 years. The central question up for debate is whether the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus had a sexual component. I begin my conversation by stating the fact that all scholars, tellers and listeners agree on: Achilles and Patroclus were exceedingly close – best friends, dearest of companions, soul mates, brothers in arms – use what terms you will. Of that there is no doubt. And when Patroclus is killed by Hector, everybody agrees that Achilles’ response to that death is the pivotal turning point in the epic.

Then I turn to a question on which scholars, tellers and listeners quite disagree. Following are the three contending theories on the Achilles/Patroclus relationship.

Most Homeric and Bronze Age scholars argue that the Achilles/Patroclus relationship was asexual. They point to the text of the Iliad, which offers not a single reference or even allusion to a sexual relationship between the two men. They further point to the Iliad to show that Achilles and Patroclus clearly have heterosexual relations with women. The scholars in this camp suggest that what causes some readers to “infer” a sexual element to Achilles/Patroclus is the written language of Homer’s Iliad. By our contemporary standards (and clearly by the standards of other time periods too), the verbal communication when Achilles and Patroclus speak to, or about each other, is romantic, florid, passionate and intimate – in a way that most societies reserve exclusively for communications between lovers. But, scholars argue, many Bronze Age works are characterized by similar language and depths of passion between males, especially between male comrades in arms. In the Hebrew story of David and Jonathan (2 Samuel 1:26), David claims that the love he had for Jonathan surpassed even the love of women. It is our contemporary sensibilities, scholars argue, that erroneously grafts a sexual meaning onto David’s claim, but there is nothing in the text to support such an interpretation.

But Classical Greek scholars and readers disagree. They argue that the Achilles/Patroclus relationship was pederastic. This way of seeing the Achilles/Patroclus relationship originated (or at least was popularized) during the Classical and Hellenistic Greek period (c. 480-146 BCE) when pederasty was socially accepted and possibly even commonplace amongst upper class Greeks. Pederasty involved an older man entering into a relationship with a young man in his teens. The older man served as a “mentor” to the younger man, introducing him into adult male society. The relationship lasted for a few years, until the younger man came of age, at which point the relationship would end. Both men either had, or would go on to have, wives and children. The pederastic relationship sometimes included a sexual element, in which the older man achieved sexual pleasure by rubbing his erect penis between the thighs of the younger man. Anal penetration does not appear to have been common in these relationships. Scholars who argue that Achilles and Patroclus were pederasts include: the philosopher Plato (in the Symposium); the playwrite Aeschylus (in The Myrmidons) and many other prominent Greek and later Roman historians. Replying to the objection that Achilles and Patroclus are never actually depicted in the Iliad engaged in sexual activity, these proponents argue that a pederastic relationship is clearly implied and obvious to anyone who examines the text.

Finally some readers argue that the Achilles/Patroclus relationship was homosexual: that the two men were gay lovers, much in the sense that we would understand such a relationship today. In Shakespeare’s play Troilus and Cressida Achilles and Patroclus are clearly depicted as gay lovers (though the term “gay” does not belong to Shakespeare’s time). I note that while Shakespeare’s play certainly does not celebrate the homosexual relationship, that is a consequence of the political, religious and social constraints of Elizabethan society – not necessarily a reflection of Shakespeare’s personal views. But I then suggest that if one wishes to see a fully celebrated and unabashedly gay interpretation of the Achilles and Patroclus story, a reader needs to move into the 21st century. Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles (2011) offers just such a treatment, and does so, in my view, quite nicely.

I conclude by asking (rhetorically) whether or not it “matters” that we get the Achilles/Patroclus relationship “right” in our telling of the story. And I argue that, save for academics and scholars, who need to worry about such things, the rest of us (storytellers and story listeners), are free to graft on to the Achilles/Patroclus relationship the “interpretation” that our communities, our cultures, our agendas, and our aspirations demand. But at all times, it is imperative to remember the central, uncontested fact of the story: when Patroclus is killed, Achilles loses the love of his life. And the grief that Achilles experiences in that moment of loss is a universal human experience that transcends all matters of mere sexuality.

Jeff

RELATED IMAGES

- BOOK A LIVE TELLING or “EDU-TAINMENT” (click here)

- NAVAL BATTLE BETWEEN TROJANS AND GREEKS, Giovanni Battista Scultori 1534

- THE AMBASSADORS OF AGAMEMNON Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres 1780-1867(featuring Patroclus in full junk shot!)

- The embassy to Achilles, Attic jug, c. 480 BCE

- JUPITER (Zeus) AND JUNO (Hera), Annibale Carracci c 1550 (Hera makes her move on her husband!)

- THE PRESENTATION OF THE PORTAIT (detail from a much larger painting) Rubens 1625 note Zeus’ eagle and Hera’s peacock

- JUPITER (Zeus) AND JUNO (Hera) ON MOUNT IDA James Barry 1773 (clearly deeply in love with each other!!!)

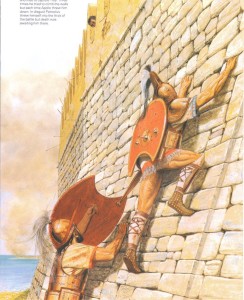

- PATROCULUS ATTEMPTS TO CLIMB THE WALLS OF TROY, Peter Connolly 1935-2012 (this isn’t going to end well!)

- THE LYRE OF PELION, (wonderful image found at Deviant Art.com; contact me if you know the artist)

- “The Song of Achilles” by Madeline Miller, 2012