THE STORY: (56 minutes) As Greek and Trojan forces openly clash on the plains of Troy the goddess Athena imbues a Greek warlord – Diomedes – with fearsome, godlike powers of combat. So with the Trojan forces in disarray and on the verge of wholescale panic, Hector decides on an audacious plan to save his army. But can Hector survive his own plan?

THE COMMENTARY: CAN WAR BE BOTH TERRIBLE and GLORIOUS? (17 minutes; begins at 56:00) This post-story commentary examines both the “glorious” and the “terrible” faces of the Trojan War. I first review the arestia of Diomedes, which dominates much of the story in this podcast episode. I point out that Diomedes’ arestia (or moment of supreme excellence in battle) follows the usual arestia pattern found in Homer’s Iliad. The hero is first imbued with god-like powers; the hero’s armour and weapons are then imbued with god-like radiance (the helmet “burns like a fire”; the bronze spear tip “is like a gleaming star”); the hero racks up an impressive kill count against worthy opponents; the hero receives a setback or injury, but recovers quickly; and the hero goes on to even greater glories before the arestia ends, and the hero becomes “normal” again. I note that in Homer only heroes are granted an arestia – rank and file foot soldiers are never so lucky. I then observe that the arestia can be understood as a “compensatory gift” from the gods to a worthy human – the compensation being necessary because the human, no matter how worthy, is ultimately doomed to die. Finally I observe that sometimes an arestia ends with the death of the hero: when a hero forgets, at the critical moment, that he is not really a god.

I then launch into an exploration of arestia in contemporary movies, noting that I could find plenty of examples of arestia in superhero or fantasy genre films, but very few arestia in movies based on real human warfare. This leads me to some hypothesizing about whether, in the 20th and 21st century, we are culturally uncomfortable celebrating “glorious war” – possibly the machine guns and poison gas of World War One dampened our enthusiasm a little? I then turn to Homer’s treatment of war in the Iliad, and observe that it is remarkably neutral and even-handed. Homer spares us none of the graphic, gory realities of the battlefield (save for a total absence in Homer of any long term, lingering, or psychological injuries), and Homer is brutally clear-eyed on the civilian price of war (rape, slavery, butchery and death). But Homer equally paints a picture of fighting men exulting in the sheer, giddy pleasure of knowing “how to step in deadly dance of hand to hand combat”. I turn the final words of my post-story commentary over to Bernard Knox, a Homer translator; because I think he says it best: “Three thousand years have not changed the human condition in this respect. We are still lovers and victims of the will to violence, and so long as we are, Homer will be read as its truest interpreter.” Homer, tr. Robert Fagles, intro. Bernard Knox, The Iliad (Penguin Classics, 1991)

Jeff

RELATED CONTENT

ANTHEM FOR DOOMED YOUTH, 1917 poem by Wilfred Owen PDF

RELATED IMAGES

- BOOK A LIVE TELLING or “EDU-TAINMENT” (click here)

- DIOMEDES WOUNDING APHRODITE Arthur Heinrich Wilhelm Fitger, 1840-1909

- DIOMEDES VS AENEAS (note Athena and Aphrodite involved) artist unknown

- THE DEPARTURE OF HECTOR FROM ANDROMACH, Gaspare Landi 1794

- HECTORS FAREWELL TO ANDROMACHE Gavin Hamilton, 1775

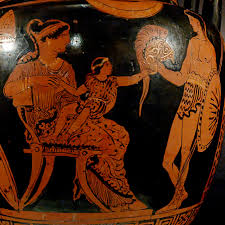

- Hector and Astyanax pottery c 300 BCE

- HECTOR AND ANDROMACHE Giorgio de Chirico 1924

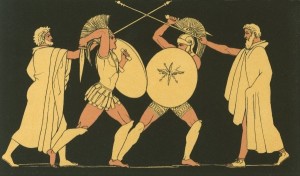

- HECTOR AND AJAX SEPARATED BY THE HERALDS artist unknown

- AJAX AND HECTOR EXCHANGE GIFTS

Greetings,

This is the first pod I have heard. Excellent. I am about half way thru. Just want to encourage and thank you. Hey, Andromache is from Thebe right?

Yes! Andromache (Hector’s wife) was from Thebes (a city that Achilles sacked).

Glad you are enjoying the podcast. Be sure to start with Episode One — you’ll have a lot more fun. Jeff